Why do so many men get away with rape? Police officers, survivors, lawyers and prosecutors on the scandal that shames the justice system

“Today in England and Wales, an estimated 300 women will be raped. About 170 of those cases will be reported to the police. But only three are likely to make it to a court of law.”

Shadow home secretary Yvette Cooper’s damning speech on the crisis at the heart of our criminal justice system in May 2022 was echoed three months later by Dame Vera Bird, the outgoing victims’ commissioner for England and Wales. In her resignation letter, Bird described a “catastrophic” period for the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) during which rape convictions have dropped to a historic low:

“As victims’ commissioner, I have shone a spotlight on the dire state of rape investigations and prosecutions … While the pandemic is abating, the criminal justice system has only sunk deeper into crisis.”

Despite initiatives such as the Operation Bluestone pilot, which seeks to develop a new way of dealing with rape cases among police forces, the shocking reality is that in England and Wales today, perpetrators of one of the gravest violent crimes – which carries a maximum penalty of life imprisonment – are very unlikely to receive any punishment at all. Many police officers and lawyers agree with the suggestion that rape has effectively been “decriminalised”.

As a former senior police detective, now criminologist, I regard the rate at which rape cases fall by the wayside at every stage of the criminal process as the greatest scandal facing our justice system. As public confidence continues to plummet, leading to ever-greater reluctance to report sexual assaults and rapes, I want to explain what’s going so badly wrong.

A deeply disturbing attrition rate

“The police investigation was shockingly bad at communicating anything with me. It left me feeling like they weren’t doing anything or didn’t care, and eventually after a year my case was closed for lack of evidence. I felt as though they didn’t even try. (Rape survivor’s account extracted from this report.)”

It’s not true to say that rapists in England and Wales are walking free from court in droves, because the vast majority never see the inside of a court building. Indeed, most rapes, legally defined as penetration with a penis without consent – the vast majority by men – are never even reported. Evidence from both the Office for National Statistics and a coalition of rape survivor charities suggests that only two in every ten women who are raped report the crime to the police.

The reasons for this horrendous statistic demand a story of their own. However, this article focuses on the 20% of rape offences that are reported in England and Wales – around 67,000 cases each year. Of these, police send only 10% through to the CPS seeking prosecution – compared with 60% in Scotland, where the prosecutor’s office has a closer relationship with the police and is held responsible for a successful investigation, rather than working independently from the police.

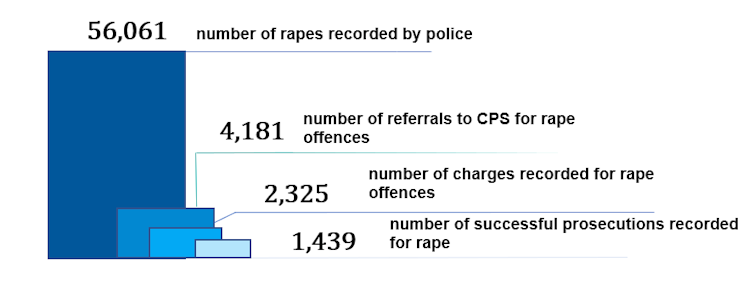

The CPS typically agrees to prosecute half the cases it sees, meaning that in England and Wales, fewer than 2,500 rape complaints (less than 5%) end up with someone being charged and taken to court, of which only 1,400 (around 2% of all reported cases) result in a guilty verdict – a disturbing attrition rate.

In all parts of the UK, very few of the rape cases that are reported to the police are “stranger rapes” – yet these are invariably the ones that receive the most publicity. In fact, the vast majority of rape cases involve people in some kind of relationship – from a long-term partner or work colleague to a more fleeting acquaintance in a pub or a nightclub.

Unlike crimes such as burglary or car theft, where a suspect is typically never seen and has no direct contact with their victim, in some 90% of rape cases the suspect is identified – usually because the victim knows their assailant. You might imagine this would improve the prospects of a successful conviction but in fact, the reverse is true.

An adversarial system

There is no point discussing what can be done to improve the attrition rate in rape cases if we ignore the daunting “cliff face” that the adversarial criminal justice system presents when these cases reach a crown court.

There are very good reasons for this system of justice, which dates back to 1765 when English judge, Sir William Blackstone, published his influential Commentaries on the Laws of England. These included a principle that remains the basis of the adversarial criminal justice system in England and Wales today:

“All presumptive evidence of felony should be admitted cautiously: for the law holds, it is better that ten guilty persons escape than that one innocent suffer.”

Most people would surely agree they don’t want a system that accepts miscarriages of justice as a consequence of fighting crime. But there are other consequences of this principle that are problematic, particularly in cases of rape.

In our adversarial system, the main job of the defence team is to represent their client. If the client tells them the victim is making things up, they will try very hard to muddy the waters, to cast the victim in a bad light, and to convince the jury that he or she may be lying to them. That is what they are paid to do.

The prospect of going through this process has consequences that ripple backwards to the very start of a criminal investigation – not least for the person who has been raped, at a time when they are likely to be enduring a deep and lasting trauma.

Everyone involved in each stage of a rape investigation and prosecution is aware of the hostile nature of the adversarial system, and what the person reporting the crime must endure if the case ends up in court. A consequence is that police officers and CPS lawyers can become despondent about the chances of their case ending with a successful outcome. According to a July 2021 report by the Police and CPS inspectorates:

“Many investigators and prosecutors told us that rape cases are ‘difficult to prosecute’. [They] were very aware of the criticism of low charge and conviction rates, and of high-profile cases that have failed. As a result, the approach adopted sometimes appeared to be more focused on thoroughly exploring the weaknesses in a case, as opposed to focusing on its strengths.”

Everything in silos

As a senior lecturer in police studies, I meet many serving detectives. For this article, I interviewed a dozen of them from four different English forces. Many appear demoralised and embarrassed that they are unable to investigate and detect more crime of all kinds.

Over the past decade, the policing system in England and Wales has been stripped of resources leading to prioritisation. One consequence is an increased reluctance to investigate “volume crimes” such as burglary, which in turn means many officers have become generally deskilled at criminal investigation. A detective inspector complained to me: “I have people joining my team from uniform who have never been to court and never taken a case through from start to finish.”

According to another detective sergeant, “everything is in silos” in his police force as a result of being so short-staffed:

“If a response officer arrests someone, they just do a verbal handover to a detective sergeant. They never investigate anything because they are so short-staffed on the shift, and are just going from job to job. There is a general lowering of investigation standards – as a workforce, we are completely deskilled.”

Because investigative skills are being lost and morale and expectations are so low – exacerbated by very public police failings ranging from the Jimmy Savile scandal to the murder of Sarah Everard by a serving Metropolitan Police officer – the ability of the police to investigate serious crimes such as rape has been severely hampered. I have heard several anecdotes from serving officers that lines of enquiry are not being followed, and that the search for evidence is less robust than it could be.

In 2020, the victims’ commissioner reported that of 500 rape survivors surveyed, many said police officers had “treated them sensitively and made them feel believed, comfortable and supported”. However, she also highlighted “many accounts of the opposite”:

“Officers who were insensitive and made the survivor feel disbelieved, judged and at fault. Some [victims] felt their experience was minimised or that police discouraged them from progressing their complaint.”

Grooming of police investigators

The vast majority of rape cases get dropped during the police investigation stage in England and Wales. Fewer than 10% of rapes reported to the police are sent on to the CPS for a charging decision. What happens during this police investigation stage so that, every year, around 52,000 rape cases fall by the wayside?

Many police forces have a group of detectives who are specially selected and trained to deal with sensitive crimes such as rape and domestic abuse. In my experience, the thoughtfulness, understanding and empathy towards victims that these detectives display is impressive and valuable.

However, most forces are not resourced well enough to provide this coverage 24/7. This means a rape survivor’s first contact with the police may be with a regular duty detective or, in smaller forces, a uniformed constable, to whom they will have to explain details of the most traumatic and embarrassing thing that has ever happened to them.

Rape figures in England and Wales (year ending March 2020):

Many rape survivors withdraw their accusations during the police investigation stage, before any charges are brought. Their impressions of the first police officers they encounter can be critical to this decision, affecting their confidence about whether to persevere with the case.

According to one officer, her force (and likely many others) splits responsibilities in a rape case. While a specially trained group of officers deal with the victim and gather their evidence in a professional and empathetic way, that package of evidence is then handed over to a regular detective who is tasked with gathering other evidence, as well as arresting and interviewing the suspect.

Under this system, another detective described a phenomenon which he called “perpetrator grooming of police investigators”:

“This can happen when a force has a specialist rape team dealing with the victim, and regular CID who then interview the suspect. Because these latter officers rarely deal with the victim, they’re only hearing the suspect’s story all the time – and it is possible for a manipulative suspect to blame the victim and get an officer to feel sorry for them.”

The victims’ commissioner’s report also highlighted this risk. A rape survivor told her researchers:

“The officer said my partner’s messages after the rape [were] “a bit cheeky”. She said he was in love with me and didn’t realise that he had done wrong. It sounded like [the officer] sympathised with him.”

Police officers are human beings. While they should not exactly reflect a cross-section of society on account of their vetting, training and monitoring, there have been recent high-profile findings of officers in London’s Met Police and other forces acting like misogynistic yobs – and worse.

In one case, the Independent Office for Police Conduct (IOPC) found 14 Met officers guilty of “multiple behavioural themes including toxic masculinity, misogyny and sexual harassment”. This report is one of the most shocking things I have ever read about police behaviour.

In July 2022, two other Met police officers were convicted of criminal conduct relating to sending grossly offensive racist and misogynistic WhatsApp texts, including threats to rape. These men were colleagues of Wayne Couzens, the serving Met officer who murdered Everard.

Of course, the vast majority of police officers will have been appalled by such behaviour. But it’s also extremely unlikely that these are the only groups of officers writing messages like this in their WhatsApp groups. And while there are 43 separate police forces across England and Wales, few among the general public will differentiate between a media report on something happening in the Met Police and their own force. In short, the damage to public confidence in the police, particularly in relation to rape cases, has been severe and will take much work to reverse.

A downward spiral of pessimism

Even if a police detective has a highly professional and victim-focused approach, for altruistic reasons they may still dissuade a rape victim from going forward with their complaint. In 2021, the Police and CPS inspectorates highlighted a risk-averse attitude to taking rape cases all the way through to court. This could be for a number of reasons I describe as a “downward spiral of pessimism”.

- Police detectives anticipate how hard it will be to persuade the CPS to prosecute the case.

- Even if it is prosecuted, they know how difficult it will be to achieve a conviction in front of a jury.

- And they understand the pain and distress the victim is likely to have to go through, often because of legal requirements with which the police themselves will burden them.

The victims’ commissioner’s survey of rape survivors includes numerous examples of investigating officers displaying a weary fatalism about the case’s chances:

“[The officers] were upfront and honest. They told me it will be his word against mine … Police discouraged me at first, outlining what I would have to go through in court in a very negative way.”

But there is another, less well understood reason for the officers’ widespread pessimism. On the few occasions that a rape allegation makes it all the way to a court room, the jury will often hear agreement from both parties that sex took place – but a dispute about whether consent was given. Detectives say consent is now the most common defence in rape cases – and the most difficult to disprove.

There has been a huge advance in DNA forensic technology since its first use in 1988. And TV programmes such as CSI Miami have alerted would-be rapists that if there has been physical contact with the victim, their DNA will likely be found by police forensic examiners. So while DNA technology is undoubtedly a deterrent for some potential perpetrators, it has also driven more rapists to rely on the defence of consent rather than no physical contact at all, and this can be more problematic for police and prosecutors to disprove. Without clear physical evidence such as injuries to the victim or a mobile phone recording, the police may believe that the chance of a jury being able to convict in a case of “her word against his” is slim.

If there has been a delay in reporting a rape, this can add to a police officer’s doubts that there could be a successful outcome. A detective highlighted a case where the female victim didn’t report it at the time because the offender was a distant relative:

“[But] after a while she found out that he was in a relationship which gave him access to another young female, so she reported her rape to try and prevent another victim. My sergeant felt that because of the delay the jury may not convict so under the CPS guidelines, they didn’t think it was worthy of putting a file in asking for a charge.”

Once again, pessimistic police officers, not trained lawyers, are second-guessing what might happen in a jury room, or what a CPS lawyer will decide in their office when they apply the “reasonable prospect of conviction” tests to the evidence bundle the police have provided.

Adding to the complexity facing these officers, it’s important to acknowledge that a very small number of reports of rape presented to the police are false. Two specialist rape and domestic abuse investigators told me that many police officers find it risky to challenge a rape victim’s story, even if they have doubts, because of a perceived fear of criticism that they are not sufficiently “victim-focused”. This phenomenon was also highlighted by a defence barrister who had been defending a woman for the crime of wasting police time after a rape report was found to be false. The barrister said it should have been obvious that the story was made up, but the police had been reluctant to challenge the account.

Read more: Victims are more willing to report rape, so why are conviction rates still woeful?

To many police officers, it can feel like a no-win situation. And the result, in England and Wales at least, is a systemic failure to see most rape reports through to the next stage of the criminal justice process, the crown prosecutor’s desk. Although an officer may have found absolutely no reason to doubt the victim’s word, they may still feel very pessimistic about the chance of a case making it all the way through to a guilty verdict.

(In Scotland, far fewer cases are stopped during the police investigation stage. This may contribute to greater confidence in the police and perhaps the criminal justice system as a whole, as evidenced by the latest Rape Crisis Scotland Report which indicates that some 70% of victims felt the police had been “supportive”.)

To charge or not to charge?

To understand what the phrase “a reasonable prospect of conviction” means in practice, I asked a former CPS chief crown prosecutor to explain how they make their decision whether or not to charge. He told me: “In theory, if it is more likely than not that a jury would convict given the evidence available, we should give them the opportunity to examine it.”

I then asked him to explain in percentage terms when a CPS lawyer would decide to prosecute a rape case:

“In theory, at 51% – that is what “more likely than not” means. But if you ask me what actually happens in practice, I expect most CPS lawyers, especially in a rape case where they know the victim will get a hard time, they probably set the bar at about a 75% chance of a conviction.”

He explained that CPS prosecutors can get criticism “from our own side” if too many cases are put through that are later withdrawn, either before or during a trial. He called this “a perverse incentive to not authorise a charge in rape cases”, since they are notoriously difficult to get through to conviction.

It is clear from interviewing police detectives that they always anticipate it will be hard to get a positive CPS charging decision. One detective sergeant said her local CPS was effectively asking the police to take responsibility for the judgment about whether a case was likely to succeed in court:

“The CPS asks us to tick a box on a form saying whether there is a realistic prospect of conviction. Often you could get an acting sergeant – who has never been to court, with no legal training – guessing what a jury might think of the victim and her credibility. They know the CPS will be picky so they decide not to send the decision to CPS. Psychologically, they feel they are less likely to be criticised for not sending a case than for sending a weak case and wasting everyone’s time.”

Again we see evidence of the “downward spiral of pessimism”, where each person is second-guessing what the next decision maker might do. But it gets worse. In her force (and this was also confirmed by an officer from another force), a detective sergeant explained:

“The CPS imposed a rule that they would only deal with charging decisions in a rape case if the police had sent a full file of evidence. It takes about 200 hours to prepare a full file, so when the sergeant has to tell a detective to spend all that time on a case … If they anticipate the CPS will reject it anyway, there is a lot of pressure to just tick a box on a form – “insufficient evidence” – and get rid of the problem that way.”

For other crimes, the police are allowed to send an “abbreviated” file to the CPS containing just the basic evidence, as long as they explain what other evidence will be available should they decide to run the case. Refusing to allow the police to do this in rape cases means that every statement must be taken, and potentially thousands of mobile phone messages must be examined, in advance of any CPS decision, at huge time-cost to an under-resourced police force.

By treating rape differently to other serious crime types it seems that, in some parts of the country at least, risk-averse CPS officials may be discouraging police supervisors from sending evidence files for a charging decision.

Since the CPS only sees about 4,000 of the initial 67,000 cases in England and Wales each year, it is perhaps easy for them to deflect criticism and say the problem of rape attrition lies elsewhere. Yet one of the reasons the CPS was set up in 1985 was to decide if there is a “reasonable prospect of conviction” and take that decision-making role away from the police.

In the face of such disastrous overall statistics, it is surely incumbent on the CPS to reclaim this role in a way that reduces police workloads – while, in cases of rape in particular, building police confidence that all cases with a reasonable prospect will indeed be prosecuted.

Why victims still don’t go ahead

There are two main reasons why victims still decide not to proceed even when a case is evidentially strong. The first is the length of time the prosecution process will take, as this police sergeant highlighted:

“We have a lot of victims who want to retract their statements because the cases are taking too long. It can easily take over a year for a case to come to court and victims just want to move on. They don’t want the court cases dominating their lives.”

It’s not just police officers who lament the long delays in cases coming to court. A criminal barrister recently wrote:

“I am increasingly numb to the cruelty of telling broken human beings that the worst thing that ever happened to them will not be resolved for years. Trial dates creep into 2023 – then, 2024.”

The UK government’s austerity policies from 2010 did not just affect the police side of the criminal justice system. Over the following decade, 164 of 320 magistrates’ courts in England and Wales (51%) were closed. According to the Law Society, by June 2021 these closures had contributed to a backlog of more than 386,000 cases in the magistrates’ courts and – because every serious case starts off with a brief hearing in a magistrates’ court – more than 58,000 delayed crown court cases, including many rape cases.

Of the few cases that end up going to court, for the first time the average duration between a rape offence occurring and the final verdict exceeded 1,000 days in 2021. Yvette Cooper commented on these delays in her speech to parliament in May 2021:

“I was told about a horrendous rape case where the brave victim was strung out for so long and the court case was delayed so many times that she gave up because she could not bear it anymore. I have heard about police officers tearing their hair out over Crown Prosecution Service delays because they know that the victim will drop out if they cannot charge quickly.”

The second major disincentive for rape survivors to proceed, even when the CPS approves a prosecution, is the intrusiveness of the process – and this has been accentuated by the mobile phone revolution. In her final report, the outgoing victims’ commissioner highlighted how rape campaigners coined the phrase “digital strip-search” to describe the police’s “routine requests” for a rape complainant to hand over their mobile phone almost immediately upon making a complaint.

Her comments followed the then-UK attorney general Suella Braverman issuing a directive in May 2022 which restated that, should a rape survivor take part in counselling before a criminal trial in England or Wales, any notes from these sessions may be examined by a police officer and possibly disclosed to the suspect’s lawyers to see if anything was said that could help their client’s defence.

Outrage over Braverman’s guidance led to 100 Labour MPs writing to the prime minister, Boris Johnson, warning that this could “cause many survivors to avoid seeking therapy, and make it more likely that cases will collapse when the prolonged stress of waiting for trials becomes too much”.

In fact, there is nothing new in this legal requirement placed upon the police. The Criminal Procedure and Investigations Act 1996 (CPIA) imposed an obligation on the police to pursue all reasonable lines of enquiry when undertaking a criminal investigation, whether these point towards or away from the suspect. If the police have any relevant material in their possession, or if they are aware that a third party holds relevant material, that material must be revealed to the CPS and then the defence team.

In the many cases of rape where the victim and defendant knew each other, any notes which may reveal the extent and nature of that relationship would be relevant for the defence team. In her 2022 guidelines, Braverman did not make counselling notes exempt from this process.

Read more: Why so many rape investigations are dropped before a suspect is charged

A police officer has to make the initial judgment about what material is relevant – the law says this is anything which may assist the defence case or undermine the prosecution case. And the police are well aware that they will be heavily criticised if they contribute to a miscarriage of justice.

But they are also clear that under our adversarial system, their decision will be subject to heavy scrutiny in the crown court if the defence barrister asks if there is any material, such as mobile phone texts or counselling notes, which that officer decided was not relevant. Many officers therefore take a risk-averse view by revealing anything to the CPS which could remotely be construed as being of assistance to the defence. As a detective inspector put it:

“We seem to lose more cases because of [a lack of] disclosure than anything else. No one gets any prizes for causing a miscarriage of justice.”

‘All my privacy was gone’

In 1996, those drafting the CPIA legislation probably did not imagine that a quarter of a century later, everyone would be carrying around storage devices that can hold 120 gigabytes of written and photographic data.

It is clear from the victims’ commissioner’s survey of rape survivors that many are very confused and upset at the intrusion into their private lives caused by handing over their phone to the police:

“I was happy to provide my mobile phone for them to download all the vile messages that supported my assaults. The police said they would download all messages between me and my ex-husband, but they actually downloaded all of my phone – every message. All my privacy was gone.”

Several survivors said the request made them feel like they were under suspicion – that they were the criminal:

“I felt anxious, confused and infuriated. I was under far deeper investigation than the rapist. [The police] had refused to take physical evidence – my clothing from the night of the attack – but wanted to investigate my private life.”

The victims’ commissioner stressed that a complainant “cannot be coerced into handing over their private digital information by threatening that the investigation will be closed should they fail to comply”. However, when the case finally comes to court, a defence barrister may well still ask for this information.

In the case of student Liam Allan, for example, his trial collapsed in December 2017 after it emerged that police had not disclosed a download of the rape complainant’s phone that had been taken during the investigation. Once the judge ordered this to be examined, it became clear that there was evidence within the text messages that the complainant had not been truthful in her evidence in court, and the case was abandoned by the CPS.

The police understandably consider it a reasonable line of enquiry to explore whether there was any previous or current relationship between victim and suspect, and so they routinely ask for a download of the victim’s phone. But the amount of data they are presented with is enormous. I was told by one officer:

“It can take days to go through texts, WhatsApp messages and photographs, checking whether there has been any contact between the two parties, and any conflicting or supporting information relating to the rape report.”

Inside the courtroom

The crown court can seem a hostile environment for rape survivors. But most judges are well aware that if they fail to give the defendant every opportunity to clear themselves, the case will end up in the appeal court – and they may be criticised for their handling of the trial. Judges are, of course, cognisant of cases like Allan’s, who might have become a victim of a miscarriage of justice because his defence team was not provided with information from the victim’s phone which would have exonerated him.

The victims’ commissioner called upon the government to “commit to free, independent legal advice for rape complainants … provided by a qualified lawyer who can counsel on matters affecting the victim’s human rights, such as disclosure”.

Excellent support and advice is already offered by organisations such as Rape Crisis, but I suggest there is merit in having an independent person, perhaps a lawyer or legal executive, appointed by the court to manage the disclosure issues around a victim’s private personal data – but this is a political issue that would require a law change, not just extra guidance.

If the UK’s system was based on the French “inquisitorial model”, it would be possible for the court to appoint its own expert that each side must rely on. The problem of intruding into a rape survivor’s privacy could then be alleviated by having an independent, legally trained expert take possession of the victim’s phone downloads, diaries and counselling notes and then, without revealing any content, provide a report assessing their relevance for the police, CPS, defence lawyers, and ultimately the trial judge. If agreed by the judge this independent report would then be binding on all parties.

Read more: How tackling ‘rape myths’ among jurors could help increase convictions at trial

In respect of certain sensitive material, such as the name of a police informant, trial judges already have a role in deciding whether it is in the public interest to disclose it to the defence team. So the principle in respect of a rape victim’s sensitive information is perhaps not that different – although expanding this system would require the Ministry of Justice to find additional budget to fund these experts.

Certainly, it is possible to make radical improvements to the criminal justice system when there is enough pressure to do so. In the late 1990s, for example, a system of trained, independent intermediaries was created to help vulnerable witnesses communicate with both the police and the courts.

A criminal justice disaster

Shamefully, the experience of rape victims whose cases actually reach the crown court is overwhelmingly negative. A report by the Centre for Women’s Justice contains harrowing quotes from survivors who have survived being cross-examined under the adversarial system. One admitted that:

“Being cross-examined was as traumatic as the rape, except with the added humiliation of a jury and a public gallery.”

Potential attempts to reduce these stresses include the extension of video-recorded witness testimony (common practice since 1991 for children and other vulnerable witnesses including rape survivors) to include the video cross-examination of witnesses by both legal teams long before the case reaches court.

The advantage for survivors is that their role in the trial would be over much sooner, which would perhaps alleviate one of the key reasons so many drop out even when the CPS wishes to send their case to court. However, these plans have been repeatedly delayed since the recommendation was first made by the Pigot Report back in 1989. Currently there are only three pilot sites trialling such a scheme for the witness category which includes adult rape survivors.

Nor will this eradicate the long wait for the outcome of the trial itself. The Labour party has announced plans to prioritise rape cases through the court system. But improving the courtroom process is far from a complete solution to our current rape crisis, of course, because few cases ever even reach a court.

The attrition rate at every stage, but particularly during the police investigation, should be regarded as a criminal justice disaster. It is so detrimental to public confidence that tinkering around the edges of a failing system is not enough.

As one detective constable said to me with a look of weary resignation: “I went on our rape team because I really thought I could make a difference to people’s lives. Yet we often seem to just let victims down and make things worse. It is so awful.”

“If you are affected by issues raised in this article and would like to talk to someone, Rape Crisis England & Wales and Rape Crisis Scotland offer telephone helplines and a network of local support centres.”

About the Author

Dr John Fox is a senior lecturer and doctoral supervisor at the School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, University of Portsmouth where he teaches students at all levels in the subjects of criminology, criminal justice and policing studies. His main research interests include police investigation, homicide and police occupational culture. John has an MSc Criminology and Criminal Justice and PhD Sociology/criminology, both from the University of Surrey.

This article originally appeared on The Conversation. Picture (c) Ian West / PA.